Models of Pastoral Care other than Parish

by Fr Eugene Stockton

We are so accustomed to the parish in the structure of the Church that we take for granted that it is the only way that the ministry of the Church can reach out to the bulk of the faithful. Now we are hearing all too frequently the word 'crisis' as fewer, aging priests and the lack of vocations threaten the closure of parishes or their amalgamation into larger impersonal entities.

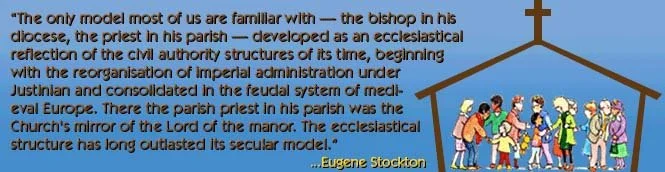

This is not a crisis for the Church. It is a crisis for a certain model of Church leadership and ministry. The only model most of us are familiar with — the bishop in his diocese, the priest in his parish — developed as an ecclesiastical reflection of the civil authority structures of its time, beginning with the reorganisation of imperial administration under Justinian and consolidated in the feudal system of medieval Europe. There the parish priest in his parish was the Church's mirror of the Lord of the manor. The ecclesiastical structure has long outlasted its secular model. The numbers problem, i.e. of too few priests to "man" all positions in the structure, is surely one of those signs of the time which alert us to the prodding of Divine Providence. Perhaps the model needs closer examination.

The history of the Church shows that models of leadership have varied greatly through the centuries, and none appears sacrosanct. The earliest model, attested to in the New Testament and Didache, had local churches enjoying both resident leadership (episcopoi, deacons) and itinerant teachers (apostles, prophets). An obvious danger in this arrangement was that of heterodox wanderers claiming to be prophets, but the Church had early established safeguards (Didache 11-13; cf Stockton 1982:32-3).

From 5th century Palestine comes a delightful account of how church ministry was remodeled, without complications, around the lifestyle of a newly converted people (Chitty 1966:83-8). A tribe of pagan Arabs had fled from Persian Suzerainty and settled in the Judaean Desert. The sheikh, Peter Aspebet, brought his sick son to the monk Euthymius: the son was healed, the tribe was converted and Peter Aspebet was consecrated their bishop. The Bishop of the Arab Encampments (Parembolarum), together with his Bedouin clergy, wandered with the nomadic tribe in its seasonal movements. Bishop Peter played an important part in the Council of Ephesus, appointed to a committee to negotiate with Nestorius.

Yves Marie-Joseph Congar O.P. [1904-1993] was a French Dominican friar, Catholic priest, and theologian. He is perhaps best known for his influence at the Second Vatican Council and for reviving theological interest in the Holy Spirit for the life of individuals and of the church. He was made a cardinal of the Catholic Church in 1994. More at Wikipedia.

As noted above, church organisation in general tended to copy the pyramid structure of the Roman Empire. At the same time, monasticism was also tending to pose a distinction between spiritual leadership (charismatic) and hierarchical authority (institutional). Yves Congar notes instances in the East and in the West (1962:129-30). In the East from the 8th century, even surviving in the staretz up to 20th century Russia, was the situation where a revered monk, rarely a priest, exercised a ministry of spiritual direction and confession, autonomously of the ordinary hierarchical structure. Similarly holiness, rather than hierarchical status, was the basis of authority in the Celtic Church up to the 12th century.

“There was no diocesan pattern, that is, there were no specific territories under the authority of bishops, but a whole complex of spheres of spiritual influence. A 'saint' had his own sphere of influence in which he was in a sense the permanent spiritual lord of a given place. A territory was affiliated to a holy man, and eventually, there was a grouping with a monastery at its centre and the jurisdiction belonged to the abbot who was often, but not necessarily, in bishop's orders. Sometimes even, as at Kildare, jurisdiction was in the hands of an abbess. Authority was attributed to the man of God, and not to a particular grade in the priestly hierarchy.”

(It is said that the local bishop may have been an ordinary monk, himself subject to an abbot or abbess.)

The crisis of the English Reformation, where the hierarchy as a whole failed the faithful, called forth a new mode of mission. One hardly supposes, in the circumstances, that searching questions were asked about jurisdiction and faculties. Danger of detection kept the priests ever on the move and limited their furtive ministry to Catholic households. Yet the Church survived and gradually returned to normalcy. This pattern was repeated in other countries during times of persecution, and also in the early stages of mission endeavour in North America and Asia.

St. Francis Xavier and his companions brought the faith to Japan in 1549 and there Christianity flourished till persecution broke out and priests were executed or expelled. Two hundred years later missionaries returned to find 50,000 Christians still true to the faith, which had been handed down from generation to generation under the leadership of 'baptisers'.

The Church in Australia was, from the first, one of laity, except for the brief ministry of the convict priest, Fr. Dixon, in 1803, until the arrival of Frs. Therry and Conolly in 1821. In the meantime, Catholics were united around the Blessed Sacrament left reserved by Fr. Dixon in the Davis home.

Village communities in some Orthodox Churches offer a model which respects the principle of local leadership and recognises the occasional need of theological expertise. When the old pappas dies, the village people elect their new pastor and send him to a seminary for a few months training (mainly in liturgy). He returns with the enormous advantage of close links with his people and with sufficient formation to perform the liturgy and to look after the ordinary pastoral needs of the villagers. At the approach of big feasts, the more highly trained “theologian priests” circulate through the countryside to hear confessions and to attend to the more demanding pastoral needs.